Rio de Janeiro food: A complete guide to what to eat

The first thing you notice about food in Rio de Janeiro is not the meals themselves, but the way their smells hang in the air: charcoal smoke drifting from a beach grill, the faint sweetness of ripe mango at a corner juice bar, the sharpness from the squeeze of lime in someone’s cocktail nearby and how cuts through the heat. Rio’s food scene sits at the crossroads of Brazil’s major cultural currents. Portuguese stews, African flavor preferences, and Indigenous ingredients share the same table, and the city treats that incredible mix as an everyday fact. This guide follows that current, from street carts to neighborhood institutions, and shows you not only what to eat but where to find it when you land in Rio hungry and curious. If you love food, think of this piece as essential reading before you decide where your first bite in the city should come from.

Table of Contents

- Traditional Brazilian food you must try in Rio de Janeiro

- Feijoada (Brazil’s national dish)

- Pão de Queijo (Brazilian cheese bread)

- Churrasco (Brazilian barbecue)

- Moqueca (Brazilian fish stew)

- Must-try street food in Rio de Janeiro

- Coxinha (chicken croquettes)

- Pastel

- Açaí bowls

- Tapioca crepes

- Beach snacks

- Brazilian drinks to try in Rio

- Caipirinha

- Chopp (draft beer)

- Fresh juices (Sucos)

- Where to eat in Rio de Janeiro: Best restaurants by neighborhood

- Ipanema and Leblon

- Copacabana

- Santa Teresa

- Brazilian food culture: What to know

- Meal times in Brazil

- Boteco culture

- Feiras (street markets)

- Practical tips for eating in Rio de Janeiro

- How much does food cost in Rio?

- Food safety tips

- Staying connected while exploring Rio's food scene

- The city you taste as much as see

Traditional Brazilian food you must try in Rio de Janeiro

Rio gives you a compressed map of Brazil on a plate. The city pulls dishes from every corner of the country and sets them down in front of you in botecos (casual bar-restaurants), kilo restaurants (a type of self-service buffet), and white-tablecloth dining rooms. But these foods are not invented to appeal to tourists. They are the classics that Brazilians themselves argue about, praise, and cook for each other on weekends. You can eat them at a plastic table on the sidewalk with a cold beer or in a room with polished wood and heavy cutlery. But the flavor stays the same: deep, layered, and rooted in a long history.

Feijoada (Brazil’s national dish)

Feijoada is the kind of dish that makes you slow down in the best of ways. It is a black bean stew thick with pork and beef: ribs, sausage, maybe a bit of smoked meat, sometimes more adventurous cuts if the cook feels generous. The pot simmers for hours until the beans turn glossy and the meats give up their toughness to become something almost silky. The classic plate arrives loaded with it. You spoon the feijoada over white rice, scatter it with farofa (toasted cassava flour), tuck in some sauteed collard greens, and finish with slices of orange that cut through the richness.

Across Brazil, feijoada has its own unofficial calendar. Many places serve it on Wednesdays and Saturdays, a habit that likely evolved because the stew takes time and works best as a long, unhurried midday meal. In Rio, some restaurants add Friday to that roster. What matters is not strict orthodoxy, but the rhythm: feijoada invites you to sit with friends, talk, watch a football match in the background, and accept that lunch might bleed into late afternoon.

To understand how seriously Rio takes this dish, climb the hill to Santa Teresa and find Bar do Mineiro. The walls are lined with photos and folk art, the tables are packed together, and the feijoada comes in no-nonsense metal pots. It feels less like ordering a menu item and more like joining a weekly ritual. You eat slowly, you add more farofa than you planned, and maybe you’ll begin to understand why so many Brazilians treat feijoada as “soul food” in the most literal sense.

Feijoada at Bar do Mineiro (Santa Teresa area)

📍 You can find Bar do Mineiro at Rua Paschoal Carlos Magno, 99, Santa Teresa — open in Google Maps.

📅 Feijoada is served on all opening days, usually from Tuesday to Sunday at lunchtime and through the afternoon.

💰 Current prices: R$95 for one person, R$155 for two, and R$280 for three (roughly US$19, US$31, and US$56).

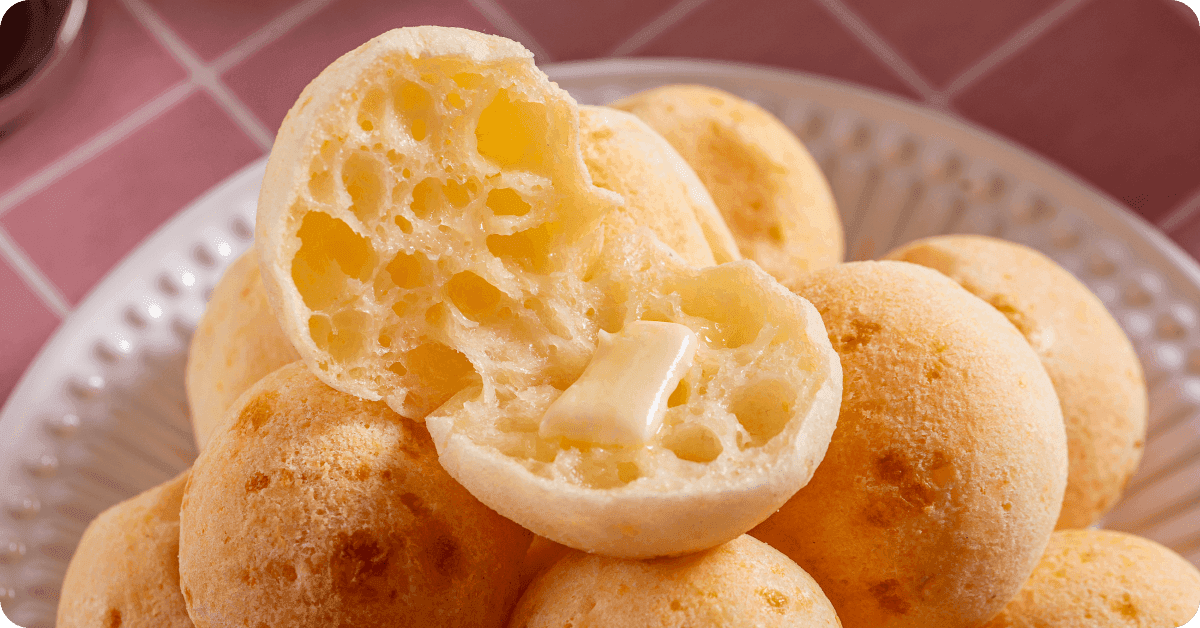

Pão de Queijo (Brazilian cheese bread)

If feijoada is a slow drumbeat, pão de queijo is a small, bright note that shows up everywhere. These are the warm, round cheese breads stacked in baskets behind bakery counters and glass cases. They come from Minas Gerais originally, a state that built its reputation on dairy and comfort food. The dough is made with tapioca flour rather than wheat, which gives each pão de queijo a chewy, elastic crumb and a naturally gluten-free claim long before anyone wrote that phrase on a chalkboard in a gentrified neighborhood.

In Rio, you encounter pão de queijo early in the day and often. A padaria in Copacabana might serve them at seven in the morning next to strong coffee and fresh-squeezed orange juice. A café in Lapa will still have them in the afternoon, ready for between-meeting snackers. In Santa Teresa, Cultivar has earned a quiet cult following for pão de queijo that comes to the table hot, with a crust that gives way to an almost custardy center. You tear one open, watch the steam rise, and for a moment the city’s noise fades behind the simple pleasure of cheese and starch done well.

Pão de queijo at Cultivar (Santa Teresa area)

📍 You can find Cultivar at Rua Paschoal Carlos Magno, 124, Santa Teresa — open in Google Maps.

🕒 The café usually opens from early morning to late afternoon, around 7:30 a.m. - 6 p.m. on weekdays and from 8 a.m. on weekends.

💰 A portion of small pão de queijo pieces typically costs around R$6-10 (about US$1-2), which makes it an easy breakfast stop or mid-walk snack when you are exploring Santa Teresa.

Churrasco (Brazilian barbecue)

Brazilian barbecue, churrasco, grew out of gaucho culture in the south, where cattle and open pastures shaped daily life. In Rio, that tradition found a more urban form in the rodízio (all-you-can-eat) steakhouse. You sit down, order a drink, and the rest of the meal comes to you on skewers. One waiter arrives with picanha (rump cap) glistening under coarse salt. Another follows with fraldinha (flank steak), another with linguiça (sausage). All that’s left for you is to decide, slice by slice, how far your appetite can go.

The choreography depends on a simple tool: a card on your table. Usually one side is green, and the other’s red. Green means “keep it coming.” Red means that, for now, you would like a truce. In between bites of meat, you help yourself at the salad bar, where you find rice and beans, farofa, vinaigrette, and a scattering of salads that give your palate a moment to rest. The experience feels indulgent, but it also recalls a more practical past. Gauchos cooked meat this way because it was efficient, direct, and social. The rodízio keeps that spirit alive in a city of high-rises and beach kiosks.

For a taste of this tradition near Copacabana, Churrascaria Palace blends old-school charm with polished service. But be careful. You might walk in thinking you will show restraint, but by the time the third cut of picanha appears, you will likely change your mind.

Churrasco at Churrascaria Palace (Copacabana area)

📍 You can find Churrascaria Palace at R. Rodolfo Dantas, 16, Copacabana — open in Google Maps.

🕒 Rodízio service usually runs daily from lunchtime into midnight (around 12 p.m. - 12 p.m.).

💰 Expect to pay roughly R$200-230 per person for the all-you-can-eat rodízio (about US$40-46), not including drinks and dessert.

Moqueca (Brazilian fish stew)

Where feijoada leans into earth and smoke, moqueca carries the flavors of the sea. It is a fish stew, usually with firm white fish and maybe shrimp, cooked gently with tomatoes, onions, bell peppers, and a generous pour of coconut milk. In its Bahian style, moqueca also uses dendê oil, an African palm oil that turns the broth a deep orange and perfumes the whole dish with a warm, nutty scent.

Moqueca comes from the northeast, especially Bahia and Espírito Santo, but Rio adopted it eagerly. In terms of comparisons to other traditional dishes, it’s lighter than feijoada yet rich enough to feel like a proper meal. The pot arrives at the table still bubbling. Rice and farofa sit on the side, waiting to soak up the sauce. You ladle out a portion and taste a food that reflects the country’s three main cultural threads at once. Indigenous people contributed the cassava that became farofa, African cooks brought dendê and the coconut milk tradition, and Portuguese influence helped standardize the stew as a centerpiece rather than a side note.

Order moqueca in Rio when the day feels hot and slow, and you need a dish that matches the Atlantic breeze rather than fights it.

Moqueca at Joaquina (Humaitá/Botafogo areas)

📍 You can find Joaquina at R. Voluntários da Pátria, 448, Cobal do Humaitá — open in Google Maps.

🕒 The restaurant usually opens from around noon (12 p.m.) and serves through the evening, making it an easy choice for both lunch and dinner.

💰 The Moqueca at Joaquina, made with fresh shrimp and classic Bahian-style seasonings and served with rice is currently priced at about R$72 (around US$15).

Must-try street food in Rio de Janeiro

The most revealing meals in Rio often come without tablecloths. The city runs on street food and quick snacks: things you eat leaning on a high counter at a boteco or sitting on the warm sand with your feet buried to the ankles. One origin story for the name of Rio's locals says that when the Portuguese built their first houses along this coast, Tupi speakers called them karai oca (“white house”), and in time the word turned into carioca, the name that still belongs to the people who were born and live in the city. Cariocas run on street food. Office workers grab salty pastries between buses, teenagers split coxinhas after class, families share pastel at Sunday markets. So if you want to understand how Rio trully eats, all you have to do is follow the smell of hot oil, grilled cheese, and sugarcane juice.

Coxinha (chicken croquettes)

The coxinha looks simple at first glance: a golden, teardrop-shaped croquette sitting in a bakery display case. Cooks shred chicken, mix it with cream cheese (often the soft, lush catupiry, a creamy cheese that Brazilians adore), wrap it in dough, then bread and fry it until the crust turns crisp and blistered. One bite gives you three textures at once. The shell cracks, the dough inside stays soft, and the filling stretches slightly from the cheese.

You find coxinhas everywhere. Botecos warm them in glass cases near the bar. Street stalls stack them on trays, ready to drop into oil when someone orders. Prices hover around R$5-8 (roughly US$1-2), so you can treat them as an impulse decision rather than a planned event. They pair well with a cold chopp or a sugary Guaraná, and they capture one of Rio’s essential truths: Comfort food needs to be close at hand.

Pastel

If coxinha is a compact snack, pastel feels more like a canvas. It is a thin, rectangular pastry that puffs when it hits hot oil and holds almost any filling. Ground beef with olives, shredded chicken, cheese, heart of palm, shrimp, even combinations like cheese and guava. The best pastel pastries come from feira stalls, where batter goes into the fryer only after you order. The vendor tucks the filling inside, lowers it into a cauldron of oil, and lifts it out when the pastry has turned blistered and crisp.

Standing at a market table, pastel in one hand and a small cup of caldo de cana (fresh sugarcane juice) in the other, you can finally feel part of the city. You bite into the corner, let the steam escape, then drizzle on hot sauce if you like more heat. Oil runs down your fingers. No one minds. Markets in neighborhoods like Glória or Flamengo still open early on weekends, and you can track the most popular pastel stalls by the crowds hovering around them.

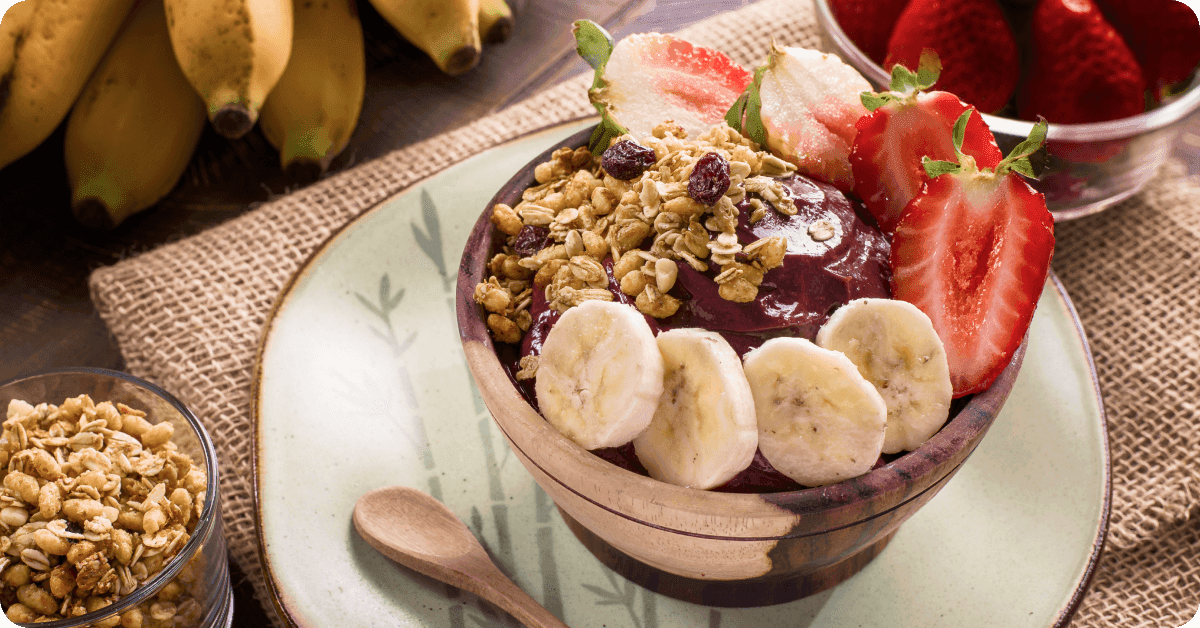

Açaí bowls

Few foods have traveled as far, and changed as much, as açaí. In the Amazon region, people long ate it as a thick, savory pulp alongside fish and cassava. Rio turned it into a cold, sweet, deeply purple bowl that sits halfway between breakfast and dessert. Frozen açaí pulp gets blended into a dense sorbet then topped with granola, banana slices, maybe honey or condensed milk. Juice bars, or sucos, serve it in plastic cups or bowls. After a day at the beach or a workout in an open-air gym, cariocas line up for it as a cooling reward.

In theory, açaí bowls count as “healthy.” In practice, they can feel indulgent once you add toppings. That tension suits Rio, a city that treats exercise and pleasure as partners rather than enemies. For visitors, an açaí stop offers a small education in how Amazonian ingredients travel south, get reimagined, and end up as part of a very different coastal ritual.

Tapioca crepes

On some corners you will see wide, flat pans dusted with what looks like snow. This is tapioca flour, hydrated and sifted so that it melts into a flexible crepe when it hits a hot surface. Tapioca crepes are made from cassava, a root Indigenous communities domesticated long before anyone called this land Brazil. Vendors spread the flour, wait for it to bind, then add fillings before folding the crepe over.

You can go sweet: Nutella and strawberry, guava paste with coconut, banana with cinnamon. You can go savory: cheese, ham, shredded chicken, egg. The texture sets tapioca apart. It chews instead of flakes, almost like a cross between a crepe and a mochi. Carts appear near metro stations, outside universities, and at night markets.

Beach snacks

The beach in Rio is its own dining room. Vendors walk the sand carrying coolers, baskets, and metal grills, turning the shoreline into a moving buffet. You might want to try some dishes once for the story, but beach snacks can easily turn into a delicious habit.

Biscoito Globo belongs in the second category. It isn’t cooked on the beach but comes in bright, prepackaged bags produced by a Rio company, yet it has become inseparable from the sandy shores. Born from cassava starch biscuits known as biscoito de polvilho in Minas Gerais, these light, puffy rings became synonymous with Rio’s beaches. They crunch then dissolve almost instantly. A red bag usually means sweet, a green bag — salty. Local wisdom says they taste best when you eat them with iced yerba-mate tea.

That mate, usually from the brand Mate Leão, comes chilled and slightly sweet, poured from large metal barrels into plastic cups. Vendors sometimes mix it with lemonade, which adds a tart edge to the herbal tea.

Next comes queijo coalho, skewers of firm white cheese grilled on portable racks until the edges blister and char. The vendor might press the cheese into oregano or brush it with a bit of sauce before handing it over. The cheese squeaks slightly between your teeth, salty and smoky.

Finally, you cannot skip coco verde. Someone chops the top off a green coconut with a few rapid machete strokes, pushes in a straw, and hands you the freshest coconut water you will ever drink. Prices for these snacks usually fall in the R$6-7 range (or about US$1.50-2).

Brazilian drinks to try in Rio

Food in Rio rarely arrives alone. Drinks carry as much meaning as dishes, and the city’s bars, kiosks, and juice stands build their own rituals around them. Some drinks are refreshing, some loosen the shoulders. All of them help you understand the city.

Caipirinha

The caipirinha might be the most efficient summary of Brazil you can hold in a glass — lime, sugar, ice, and cachaça, the sugarcane liquor that smells faintly of grass and heat. Bartenders muddle the lime with sugar, add ice, pour in cachaça, and stir until everything turns cold and slightly cloudy.

Anthony Bourdain once called the caipirinha “a utility beverage good for any time of day, or any social occasion,” and he was only half joking. On Rio’s beaches, you meet the caipirinha man weaving between umbrellas. In botecos, you see tumblers of it sweating on the table next to plates of coxinhas. It suits feijoada, churrasco, and pastel equally well. And it goes down easier than its strength suggests.

Chopp (draft beer)

In Rio, asking for a beer often means asking for chopp, unpasteurized draft beer served very cold in small glasses so that it stays crisp to the last sip. You hear the word in botecos when someone waves at the bartender and orders “um chopp bem gelado.”

Rio’s craft beer scene has grown in recent years, with microbreweries and specialty bars offering IPAs, stouts, and sours, but chopp still anchors the city’s social life. Prices usually range from R$10-15 (roughly US$2.50-4) in casual places. That makes it easy to sit for hours, matching your pace to the flow of conversation rather than the push of a clock.

Fresh juices (Sucos)

Juice bars, or casas de suco, treat fruit with the same seriousness that wine bars give bottles. Counters line up blenders, piles of ice, and mounds of produce: mango, pineapple, passion fruit, guava, cashew fruit, acerola, papaya. You can order each fruit alone or ask for combinations. Sugar is optional. Many locals prefer juices “sem açúcar,” letting the fruit stand on its own. After a few days in Rio, you start to understand why these sucos matter. They connect city dwellers to the country’s abundance in a direct, daily way.

Where to eat in Rio de Janeiro: Best restaurants by neighborhood

Rio is a city of neighborhoods, each with its own logic and appetite. Beaches define some, hills shape others, and restaurant culture shifts accordingly. You can eat well almost anywhere, but knowing a few anchor spots in key areas helps you move through the city with a little more confidence.

Ipanema and Leblon

Ipanema and Leblon are two popular, upscale neighborhoods that share the same curve of sand, with apartment buildings and cafés running back toward the lagoon. The mood is polished but relaxed, and you feel that mix when you walk straight off the beach into Zazá Bistrô Tropical, where an old house turns into a dining room for creative Brazilian cooking. A lemon risotto with slow-cooked lamb or fish with coconut and herbs shows how the kitchen lets different regions of Brazil talk to each other on a single plate.

For sushi, Gurume leans on the strength of Brazil’s Japanese community and serves clean, carefully cut fish that resets your palate after days of stews and barbecue. Mornings belong to Baked, a bakery where strong coffee meets croissants and pão na chapa (toasted bread with butter). When you want something sweet and unmistakably local, Brigadeiros Fabiana D’Angelo specializes in brigadeiros (chocolate truffles) rich enough that you plan to eat one and usually reach for a second.

Copacabana

Copacabana, with its black-and-white promenade, balances tourists and longtime residents in the same blocks. That mix shows up at Bar Café Rex, a straightforward spot that opens early, serves proper Brazilian breakfasts, and keeps regulars coming back for daily specials like oxtail stew or sausage with onions and peppers. The decor is simple, the service direct, and the food comforting.

Nearby, Baixela draws people in with frango à parmegiana, a breaded chicken cutlet under tomato sauce and melted cheese, usually served with rice and fries, which feels perfect after a long swim. Along the sand, kiosks cook grilled fish, pastel, and pour cold beer. The safest bet is to choose the kiosk busy with locals speaking Portuguese instead of those that have people waving laminated menus at the promenade.

Santa Teresa

Perched on a hill above downtown, Santa Teresa feels like a small town folded into the city, with narrow streets and trams passing overhead. Bar do Mineiro sits at its heart, serving one of Rio’s most loved feijoadas alongside other classics in a space that looks like an upscale version of a traditional boteco. The plates are generous and a feijoada lunch here can easily turn into your only plan for the day.

A short walk away, Cultivar rewards early mornings with strong coffee and excellent pão de queijo as the neighborhood wakes up. Casa Nossa Lounge offers dinner in a garden setting, with Brazilian staples and more inventive dishes eaten under plants instead of bright signs.

Brazilian food culture: What to know

Understanding Rio’s food culture helps you choose well, relax into the local flow, and avoid small surprises that might distract from a good meal. A few basics about timing, botecos, and street markets go a long way.

Meal times in Brazil

Daily meals follow a pattern that puts more weight on lunch than many visitors expect. Breakfast (café da manhã) stays light, lunch (almoço) often serves as the main meal, and dinner (jantar) slides later into the evening. Many restaurants close on Monday, so planning ahead saves disappointment.

You can keep this rough outline in mind:

Breakfast (café da manhã): 7-9 a.m., usually coffee with milk, bread, simple pastries.

Lunch (almoço): 12-2 p.m., often a full plate with rice, beans, a protein, and salad.

Dinner (jantar): 7–10 p.m., with 9 p.m. reservations common in busier areas.

Closures: Many restaurants close on Monday, so always check opening hours before you go.

If you like to plan around meals, our international travel checklist will help you eliminate all other logistical worries and help you fit Rio’s eating hours into what is sure to be a packed trip.

Boteco culture

A boteco is a casual bar-restaurant where aluminum tables spill onto the sidewalk and conversations mix with the sound of frying oil. Locals meet friends, watch football, and build meals from petiscos (small plates) such as fried sardines, bolinhos de bacalhau (salt cod fritters), coxinhas, and pastel. The focus stays on sharing and talking rather than on three-course formality.

The table usually orders several plates for everyone instead of separate main courses, and drinks set the tempo: cold chopp (draft beer), simple caipirinhas, sometimes a bottle of cachaça poured into small glasses. Spend an evening in a boteco away from the main tourist streets, and you see how long people linger, how often “saúde” (“to your health”) rises with clinking glasses, and how easily food and conversation blend.

Feiras (street markets)

Weekly feiras (street markets) bring fresh produce, fish, meat, and cooked food into each neighborhood on specific days. Trucks arrive before dawn, stalls go up, and by late morning the street turns into a moving corridor of shopping and snacking. Locals stock up for the week and pause for pastel with sugarcane juice between stalls.

A few markets stand out: Feira da Glória on Sundays for its wide food choice, Feira de São Cristóvão for northeastern dishes and music in a permanent pavilion, and Feira de Ipanema on Sundays for crafts with a small side of snacks. Walking through these markets gives you a clearer sense of how cariocas eat at home and offers a natural setting to work on new food vocabulary.

Practical tips for eating in Rio de Janeiro

You can eat well in Rio on a reasonable budget if you understand price ranges and pace yourself. A little planning makes room for more spontaneity once you arrive.

How much does food cost in Rio?

Food prices vary by neighborhood and style, but Rio rewards curiosity more than high spending. Street stalls, simple restaurants, and mid-range dining all offer good value when you know what to expect.

You can roughly expect these ranges:

Street food: R$5-15 (US$1-4) for items such as coxinha, pastel, tapioca crepes.

Casual restaurant meal: R$30-60 per person (US$7-15) for a main and a drink.

Mid-range restaurant: R$80-150 per person (US$20-38) if you add starters or dessert.

Fine dining: R$200+ per person (US$50+) for tasting menus or high-end spots.

Beer/chopp: R$10-15 (US$2.50-4) in most bars and botecos.

If you like to budget in advance, Saily’s guide on how much data you need on your phone pairs well with your food budget planning, so you can estimate both what you will eat and how much you will use your phone in a typical day.

Food safety tips

Locals rely on Rio’s street food and simple restaurants, so most vendors have every reason to keep basic standards. You have a better chance of avoiding a stomach bug when you favor busy places, fresh oil, and simple precautions.

A few guidelines help:

Water: Tap water is treated, but most people drink filtered or bottled water. Ice in restaurants and bars usually comes from filtered water.

Street food: Choose busy stalls with high turnover and food cooked to order, especially for fried items like pastel and coxinha.

Fruit: Wash or peel fruit you buy whole at markets. At juice bars, you can ask for “sem gelo” (no ice) or “sem açúcar” (no sugar) if you prefer.

Trust your instincts: If something smells off or looks tired, walk away. Rio always gives you another option a few doors down.

If you keep these simple habits in mind, you can relax into the city’s food scene and focus on what matters: tasting as much of Rio as your appetite allows.

Staying connected while exploring Rio's food scene

Good meals in Rio often start with a search. You look up which boteco locals like in a new neighborhood, check which day the nearest feira sets up, or save a place in your list of favorite travel apps. Saily’s guide to staying connected while traveling and its overview of the best travel apps help you decide which tools deserve space on your phone before you leave home.

Once you land, reliable mobile data matters more than café Wi-Fi. In Rio, a digital plan usually feels easier than scouring the city for physical SIM cards. An eSIM for Brazil keeps your phone online as you move between Ipanema, Copacabana, and Santa Teresa, so you can check maps, read menus, and follow recommendations without thinking about local shop hours.

When you’re ready to set it up, download the Saily eSIM app, pick a plan for Brazil, and activate it before your first pastel or feijoada. After that, you spend less time worrying about your connection and more time deciding what to eat next.

Need data in Brazil? Get an eSIM!

1 GB

7 days

US$3.99

3 GB

30 days

US$9.99

5 GB

30 days

US$13.99

The city you taste as much as see

Rio’s food scene feels like the city itself: bright and noisy, full of small surprises that stay with you long after you leave. The best way to eat in Rio blends approaches. Spend one day at a neighborhood boteco ordering petiscos until the table disappears under shared plates. Book a rodízio churrascaria and let the skewers keep coming. Walk through a feira on Sunday and follow your nose from stall to stall. Sit on the sand with Biscoito Globo crumbs on your fingers and mate in your cup, then look up ideas for things to do in Rio de Janeiro once the sun dips below the horizon.

Come hungry, stay open to the city’s flavors, and treat each meal as another way to map Rio. By the time you leave, you will remember the views and the music, but you will remember the food just as clearly.

FAQ

Related articles